This was the first fully independent overall evaluation of CDB PBL, carried out by its Office of Independent Evaluation (OIE). It assessed the nearly $550 million in PBL to 12 borrowing members approved over the period 2006–2016, employing a significantly higher level of effort than the three earlier reviews of 2010–2012.

Objectives of the Evaluation

The evaluation’s objectives as stated in its terms of reference were to assess:

- the need for the PBL program,

- the relevance of the PBL program to BMCs,

- the achievement of results for BMCs,

- the design and implementation of the PBL program,

- the extent to which the PBL compares with international experience, and

- ways in which the program can be improved to support CDB’s strategic objectives.

Evaluation Approach and Methodology

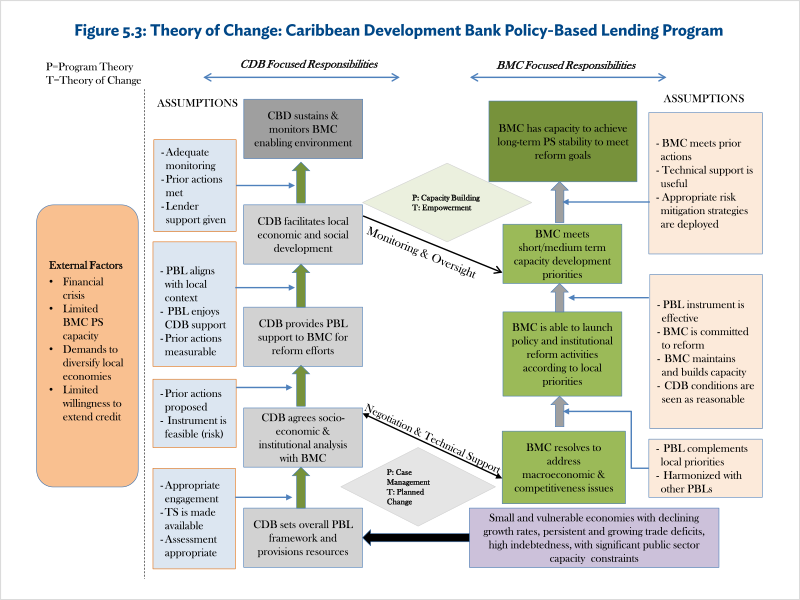

This was a theory-based evaluation, with a reconstructed theory of change for the PBL program (Figure 5.3), validated with stakeholders. It tested numerous assumptions that underlay the program.

BMC = borrowing member country, CDB = Caribbean Development Bank, PBL = policy-based lending, PS=public sector, TS=technical support

Figure 5.3 suggests that the logic of CDB’s PBL program has two parts: (i) the conditions set by CDB, and (ii) the conditions actually implemented by BMCs. CDB created the PBL initiative to enable BMC governance reforms that would not otherwise occur. Specifically, PBL was intended to assist “small and vulnerable economies with declining growth rates, persistent and growing trade deficits, high indebtedness, with significant public-sector capacity constraints.13Caribbean Development Bank. 2013. Policy Paper: Framework for Policy-Based Operations - Revised Paper. BD_72/05 Add. 5”To support such economies, CDB prepared funding contracts with conditions negotiated with borrowers to address policy-based reforms. CDB assessed whether BMCs were carrying out the conditions of these contracts through regular monitoring and oversight as shown by the cross arrows between the two causal pathways in the figure. For their part, BMCs accepted the conditions contained in those contracts with the long-term objective of ensuring macroeconomic stability and public capacity to meet their development goals.

In program theory literature, the change theory that best explains whether CDB can create such conditions is called “planned behaviour.” This theoretical framework suggests that if CDB creates appropriate application, review, and implementation processes for its PBL program, and there is a clearly stated need and rationale for the PBL intervention, then borrowers will utilize the program to buttress their own reform efforts and prevent breakdowns or crises in their local governance systems. For their part, BMCs will not successfully effect the reforms unless conditions are built that maximize their room or flexibility for programs of reform based on their own identification of needs. Such flexibility provides the local confidence and commitment needed to respect PBL agreements.

Extensive evidence was gathered to test the assumptions in the theory of change (Table 5.5). This included in-depth case studies of PBL operations in Barbados, Jamaica, Grenada, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines; a meta-analysis of PBL experience at other MDBs; extensive interviews with BMC and CDB officials; and analysis of secondary (mostly macroeconomic) data.

Table 5.5: Assumptions Tests by Evaluation Criterion

|

Assumptions Tests |

|

|

1: Relevance of the PBL program |

|

|

If the first set of assumptions holds, examine the next questions. |

|

|

2: Appropriateness of the conditions |

|

|

If the first and second sets of assumptions hold, examine the next questions. |

|

|

3: Observable effects |

|

PBL = policy-based lending, PBL = policy-based operation.

Findings and Conclusions

Need, relevance, and rationale. It is beyond dispute that MDB lending has been important to BMCs, enabling them to address fiscal pressure and debt management, as well as to encourage economic and social sector reforms. However, different parties emphasized different aspects of the instrument. Borrowers tended to be driven by short-term fiscal pressures, particularly in the aftermath of the 2007–2009 financial crisis. PBL support played a role in helping some of them through that period, and at times they agreed to reform programs that they did not entirely buy into. For their part, lenders (including CDB), while recognizing fiscal exigencies, understood the PBL to be primarily an instrument that provided incentives to implement reforms. At times they required large numbers of “prior actions” from BMCs as conditions of PBL support.

To some extent this difference in perspective had to do with sequencing: in one view relieving fiscal pressure first to allow the space to eventually undertake reforms; and, in the other, adopting reforms that will eventually help open fiscal space. While these views could co-exist in the broad space of acknowledged need for PBL lending, their differences did have implications for the expectations and approach to PBL negotiations by the respective parties.

A number of MDBs and other partner organizations—including the World Bank, IMF and IDB— brought significant funding to policy-based lending in the region. Respondents had clearly reflected on the appropriate role and value added of CDB among these larger players. They alluded to CDB’s more detailed understanding of BMC contexts, its closer working relationships with governments, and the potential for brokering harmonized reform packages that included non-economic governance elements.

Planning and design. The quality of the process by which borrowers and lenders came to an agreement on the design of an intended reform program was an important predictor of eventual success. The evaluation observed that in the first generation of PBL operations there was a perceived imbalance in negotiating leverage between CDB and borrowers (favouring CDB). As a result, the ownership of the prior actions by the BMCs and their commitment to expected reform outcomes were sometimes less than complete. This was compounded in cases where CDB’s consultation did not involve a sufficient range of stakeholders, particularly those who would either have a role in implementing reforms or would be affected by them. Not hearing these views at the outset came at the cost of lack of buy-in or even resistance to intended reforms during implementation. More recent PBL design processes had performed better in this regard.

Apart from the process of arriving at a design, the actual nature and number of prior actions and expected reform outcomes were important determinants of effectiveness. Again, it was observed that there was an evolution from earlier to more recent PBOs. Pre-2013 PBOs tended to require larger numbers of prior actions across multiple sectors, and these often lacked a clear causal linkage to the higher-level expected reform outcomes. BMCs felt that prior actions did not always reflect national reform priorities, and that the cost of delivering on them sometimes exceeded the value of the PBL on offer. More recently, there have been examples of PBOs with streamlined prior actions in fewer areas. These actions have been better calibrated to the scale of assistance being offered, and more likely to be achieved. There has also been some evidence of successive PBOs building on earlier efforts, with prior actions requiring incremental progress from earlier to later loans.

Assessing at the outset whether borrowers had the capacity to implement intended reforms was a necessary element of good PBL planning. Providing TA responsively during implementation to address bottlenecks was also important. To date, this has not been an area of strength for CDB.

Harmonization of CDB PBOs with those of other MDBs became stronger over the evaluation period. However, an unanticipated consequence of this harmonization has been that closely synchronising CDB’s prior actions with those of other lenders has somewhat limited CDB’s flexibility to tailor its own offerings. Such tailoring could grow out of CDB’s particular understanding of BMC context, or its interest in promoting reforms focused on non-economic areas.

Implementation. The timeliness of fund disbursement under the PBL mechanism was efficient. That said, there were some instances of tranche payment in the absence of all prior actions being met (which is likely to have been related to earlier findings regarding numerous conditions and national capacity constraints). CDB’s monitoring of PBOs was inconsistent. Project supervision and completion reports were sometimes missing, and monitoring was more oriented toward verifying completion of prior actions than to assessing progress towards reform outcomes. Evidence was not always available to corroborate project completion report statements.

The quality of PBL results frameworks was not optimal. The link between prior actions (outputs), and economic, sectoral, and institutional reforms (outcomes) was not always clear. Proposed indicators and targets were not necessarily good measures of the outcomes with which they were (or should have been) associated. BMCs lacked the capacity to report on the range of expected results. Statements of risk tended to be generic across PBOs, missing the need for mitigation strategies specific to each PBO’s expected outcomes and national contexts.

The revised framework document of October 2013 placed renewed emphasis on the longer-term reform orientation of policy-based lending, and the value of programmatic PBL. At the same time, there are varying stages of readiness for reform implementation across the region, and a menu of PBL instruments, including multitranche PBOs, may be needed to respond to different situations.

Results achievement. Completion of PBO prior actions for three of the four case study countries (Barbados, Jamaica, and Grenada) was verified. This totaled 113 prior actions across five PBOs. In the fourth case study country (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), completion of 19 out of 23 originally planned prior actions was verified; the other four were waived with Board approval to allow a second-tranche disbursement.14In view of the challenging economic circumstances at the time, and the otherwise positive reform trajectory, the CDB Board authorized disbursement of the second tranche of the 2009 PBL, notwithstanding delays in completion of four prior actions. A separate 2010 PBL operation for St. Vincent and the Grenadines used an unusual formulation involving six prior actions and seven post-disbursement conditions or indicators. Completion of the prior actions was verified at the time of the evaluation, along with four of the post-disbursement conditions.Among the short-term outcomes of the PBL operations were:

- debt management improved;

- fiscal space created that allowed BMCs to bolster social program reforms or reduce economic stress on individuals and families;

- conditions for investment improved to bolster key industries (such as tourism, by reducing wait times at border crossings, which could be attributed in part to PBL); and

- critical management systems such as audit, budgeting and planning improved, contributing to increased public sector management efficiency.

Because of the number of causal factors in play, including support from other PBL lenders and global economic events, it was difficult to attribute medium-term outcomes directly to CDB lending. Nonetheless, BMC officials across all case studies indicated that a coordinated, targeted, and ongoing program of reform supported by lenders such as CDB had ensured momentum, leading to improved economic and social program performance. For example, Jamaican respondents indicated that its 2008 PBL was, “a critically important intervention in Jamaica, and with the support of other MDBs helped to identify first generation structural reforms on which the recent fiscal gains have been premised.”

Generally, however, it was not feasible for the evaluation to gather a sufficient amount of directly attributable evidence to support statements of causal linkage between CDB’s PBL support and higher-level medium-term outcomes. This is a common difficulty in PBL assessment across MDBs, although as mentioned above an improvement in CDB’s specifications, measurement, monitoring, and reporting on results would help.

Summary Comments and Recommendations

Over the 10 years since the introduction of PBL at CDB, there had been an evolution in practice that reflects CDB’s learning and experience in managing the instrument, and its observation of how other MDBs also manage PBL. The loans addressed an evident need among BMCs.

The findings and conclusions of this evaluation, based on evidence generated from the document review, documented case studies, and a wide range of interviews, suggested that several key factors increased the likelihood of PBL operations achieving their desired results. These were:

- clear objectives and results logic, with indicators and targets that can be measured and verified;

- a selective focus on a manageable number of expected reform outcomes;

- agreement on a limited number of prior actions that are clearly linked to those outcomes;

- good understanding of external risks, and elaboration of mitigation strategies;

- an engagement process with BMCs that engenders ownership and commitment on the part of borrowers;

- a menu of PBL options that offers the right instrument calibrated to borrowers’ reform readiness;

- an understanding of national capacity constraints and, where needed, provision of affordable TA to address them;

- designation of an identified champion in the national public service with responsibility and authority for achieving reform results; and

- consistent monitoring to identify when conditions are met, and the degree of progress towards reform outcomes.

Although the evaluation found that CDB’s PBL was increasingly taking account of these factors, it offered the following recommendations to encourage further progress.

(i)CDB should review its practice of management for development results (MfDR) in the PBL program. It should ensure that its design process respects good MfDR practice, with clearly stated expected outcomes and indicators that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). The robustness of the results framework should be the primary criterion for quality at entry. Where necessary, staff responsible for PBL design and monitoring should have access to training in MfDR techniques, as well as occasional expert advice from a results specialist.

(ii)CDB should develop more tailored risk mitigation strategies. To date, such strategies have tended to be generic across PBOs. Instead, they should be more closely matched to the specific circumstances of the national context and reform program.

(iii)CDB’s policy-based lending should focus on a limited number of key outcomes, with prior actions that are causally linked to them. The selection of outcomes should take account of: (a) the limited size of CDB’s PBL loans, (b) BMC priorities and CDB’s own country strategy, and (c) an agreed longer-term reform program in mind. This focus should ideally be maintained over time, with prior actions in successive PBOs building incrementally on one another.

(iv)National ownership and leadership are indispensable to the success of development reform programs. CDB should facilitate these to the greatest extent possible through collegial engagement with BMCs in PBL design and implementation. This will require consultation with a sufficient breadth of national stakeholders, at both leadership and implementation levels, to gain commitment and follow through on reform objectives and prior actions. A good practice to be encouraged is the designation of a “champion” from the BMC’s public sector for implementation of targeted reforms.

(v)Small economies experience serious capacity constraints in attempting to implement reform programs. These need to be anticipated and responded to as part of an effective PBL program. Relative to other MDBs, CDB has an intimate understanding of the contexts and constraints of its BMCs. Yet it has carried out only limited needs analysis or uptake of CDB TA in connection with its PBL loans. CDB should investigate the reasons for this, ensure that potential TA requirements are well analyzed at the design stage, and that flexibility is shown when they are offered during implementation.

(vi)Different countries find themselves at different stages of readiness for PBL-supported reform programs. Although the 2013 revised framework for PBL lending emphasized placing loans within a longer-term reform context (through a programmatic series approach), some BMC stakeholders contend that multitranche PBL may continue to be well suited to BMCs requiring more structured and predictable prior actions. CDB should ensure that the right PBL instrument is matched to each reform context.

(vii)Monitoring and completion reports are important parts of the effective implementation and accountability of the PBL program. CDB should ensure that these tasks are consistently carried out, and that they have a results focus, for all PBL. This should go beyond verifying that prior conditions have been met, and should assess the extent to which these actions are contributing to reform outcomes. CDB should also consider extending monitoring efforts beyond the timeframe of PBL disbursements. The outcomes of interest are, after all, medium- and longer-term reforms, and CDB will wish to track these as part of its overall country strategy process.

Management Response

Management expressed general agreement with the findings, conclusions, and recommendations of the OIE evaluation, with one area of exception. It felt that evaluators had underappreciated the extent of staff engagement with borrowers in arriving at agreed prior actions and reforms, and thus also understated the degree of national ownership of PBL-facilitated reform programs. It acknowledged, however, that consultation processes could have been better documented, that results frameworks should have more clearly established the logic of the links between prior actions and reforms, and that monitoring could be improved.

Management accepted all recommendations and provided a time-bound action plan for their implementation. The Oversight and Assurance Committee, a subcommittee of the Board of Directors, annually monitors completion of these actions.

- 13Caribbean Development Bank. 2013. Policy Paper: Framework for Policy-Based Operations - Revised Paper. BD_72/05 Add. 5

- 14In view of the challenging economic circumstances at the time, and the otherwise positive reform trajectory, the CDB Board authorized disbursement of the second tranche of the 2009 PBL, notwithstanding delays in completion of four prior actions. A separate 2010 PBL operation for St. Vincent and the Grenadines used an unusual formulation involving six prior actions and seven post-disbursement conditions or indicators. Completion of the prior actions was verified at the time of the evaluation, along with four of the post-disbursement conditions.