OVE’s analysis of the design of PBL focused on the evolution and nature of policy conditions, the vertical logic of the programs, and the extent to which PBL was accompanied by other IDB support. When looking at the evolution of policy conditions, OVE considered all PBL operations approved between 1990 and 2014, in order to gain a longer-term perspective. For a more in-depth analysis of the nature of policy conditions, and the complementarity between PBL and parallel IDB support, OVE focused on PBL operations approved in the decade leading up to 2015. In order to conduct this analysis, OVE drew a stratified random sample of 40 policy-based programs from the universe of PBL operations approved between 2005 and 2014 in four thematic areas: public sector and economic management, social sectors, financial sector, and energy. The sample encompassed 70 multitranche and programmatic loans in 18 countries and covered 34% of all programs approved over the time period. Analysis of policy matrices was supplemented by information from pertinent OVE country program evaluations and interviews with IDB staff and country stakeholders. To review the complementarity between PBL and parallel IDB support through technical cooperation grants or investment loans, OVE focused on all 82 programmatic PBL series (equivalent to 144 PBL operations) approved between 2005 and 2014.

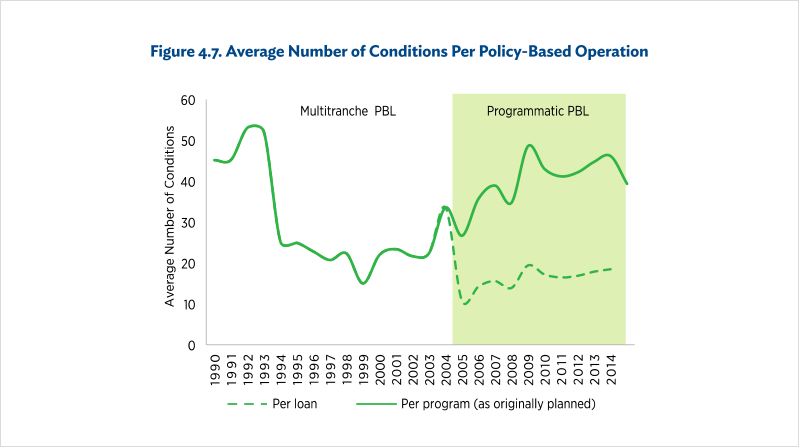

The number of conditions at the program level increased over time. In the early 1990s, the average number of conditions per loan was roughly 50, and that figure fell by half between the mid-1990s and 2004. In line with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Paris Declaration in 2005, the introduction of the programmatic modality further streamlined conditionality at the loan level (Figure 4.7). However, at the program level, the average number of conditions increased after 2005, offsetting the streamlining gained at the loan level10For multitranche PBLs, the average number of conditions per loan was found to have increased from 23 to 32.. There were no significant differences in the number of conditions across thematic areas or regions.

PBL = policy-based lending.

Note: The graph shows the average number of conditions per multitranche policy-based loan for 1990–2004, and per programmatic PBL series from 2005 onwards, at both the loan and the program level (as originally expected). Figures at the program level are based on the programmatic PBL series’ initial year.

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE).Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB. Document RE-485-6. Washington, DC: IDB. https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-id

To determine to what extent PBL-supported policy conditions had sufficient depth to trigger long-lasting policy and institutional changes, OVE’s analysis reviewed the content of each policy condition and assigned one of three categories to it:

- Low-depth. Conditions that would not, by themselves, bring about any meaningful changes. Low-depth conditions are usually process-oriented and often involve the preparation of action plans or strategies and the announcement of intentions.

- Medium-depth. Conditions that can have an immediate but not a lasting impact. These include conditions calling for one-off measures that can be expected to have an immediate and possibly significant effect, but that would need to be followed by other measures for this to be lasting. Submission of draft legislation to Congress, reaching a target or benchmarks, and organizational changes are examples of medium-depth conditions.

- High-depth. Conditions that could, by themselves, trigger long-lasting changes in the institutional or policy environment. Conditions in this category include legislative changes, government decrees, or lower-level actions that complete a critical reform process. High-depth conditions also include measures that require that certain fiduciary measures be taken regularly or permanently, even when legislation is not needed.

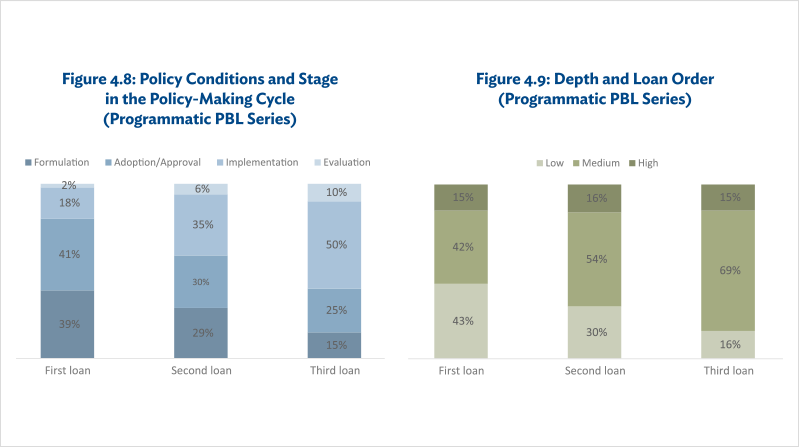

This analysis was supplemented by an assessment of the programs’ overall vertical logic and coherence. OVE evaluated the sequencing of the conditions across PBL tranches or across individual loans in a programmatic PBL series by looking at the extent to which the policy conditions included in each tranche of a multitranche PBL, or in each loan of a programmatic PBL series, followed a logical sequence over time by supporting different stages of the reform process cycle (i.e., formulation or design, adoption or approval, implementation, monitoring and evaluation). OVE also assessed the program’s vertical logic: the coherence between conditions and the reform program objectives and expected results. While OVE’s analysis of the depth of policy conditions and their sequencing allowed it to gauge the progress of the reform program supported by PBL, the methodology did not measure IDB’s technical additionality to the reform program or the extent to which the impetus for reforms could be traced to IDB actions.

Most conditions involved policy or regulatory measures, while a small proportion focused on organizational changes at public agencies. OVE found that almost 80% of conditions in the sample supported policy reforms, ranging from the design of a new payment scheme for a social program to the approval of fiscal responsibility legislation. The rest promoted changes in the structure, responsibility chain, and/or institutional capacity of public agencies, such as the creation of a public health unit in the Ministry of Health or the formulation of a code to define the structure and processes for a public agency.

Most conditions were low- or medium-depth; they helped set in motion policy reforms but could not by themselves effect lasting changes. Almost a third of conditions in both the multitranche PBL and the programmatic series reviewed were low-depth, calling for basic one-off measures or simply expressing intentions. For example, a condition would commit a line agency to an independent operational audit of a feeding subsidy or call on an agency to prepare terms of reference for the design of a methodology to analyze the outcomes of a national investment plan. It is questionable whether such measures are in line with IDB’s guidelines, which stipulate that PBL conditions should be essential for the achievement of expected results. Only 15% of the conditions in the sample were high-depth, for example the elimination of government budget support for state-controlled enterprises or the adoption of revised targeting mechanisms for a school feeding program. No major differences in the depth level of conditions were found between multitranche PBL and programmatic PBL series.

Sequencing of PBL conditions followed the stages of reform cycles and tended to gain in depth as the reform process advanced, but the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) stage was seldom included. OVE classified the conditions in each operation according to the milestones in a policy reform cycle (formulation, adoption, implementation, M&E) that they supported. Not surprisingly, conditions in the first tranche or loan tended to focus on earlier stages of a policy reform process, while a larger proportion of conditions in subsequent tranches or loans tended to focus on implementation (Figure 4.8). Conditions gained in depth as the program advanced. For example, 43% of conditions in the first loans of programmatic PBL series were low-depth, while this proportion decreased to 30% in the second loan and to 16% in the third (Figure 4.9). According to OVE’s analysis, the reviewed conditions were generally relevant to the programs’ objectives, although they were probably insufficient to attain the expected outcomes. Less than 6% of the conditions reviewed included provisions linked to the last stage of a reform process—M&E. Programs in the social sectors were more likely to include M&E conditions, especially when compared with those in the financial sector (0.8% of conditions).

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight(OVE). Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB. https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-idb

Programs with a larger number of conditions tended to have a greater share of low-depth conditions. This suggests that IDB could in many cases have been more parsimonious with policy conditions and focused on measures that were critical to achieving the desired results. Similarly, OVE found no correlation between loan amount per capita and how ambitious the reform program was, nor did it find any correlation between loan size and the number of policy conditions. For example, the first loan of a program to strengthen the public finance system in Mexico in the amount of $800 million had 15 policy conditions, while the second loan in support of a water resources reform program in Peru in the amount of $10 million had roughly the same number. These findings are consistent with IDB’s policy-based lending guidelines, which state that the size of the loan is not necessarily related to the cost of the policy reforms or institutional changes supported by the PBL, but rather to development financing requirements.

The depth level of reform programs varied across and within countries; in general, programs in the financial and energy sectors tended to have more depth. When analyzing differences in the depth level, sharp differences across countries were detected. For example, about 22% of the conditions in Peru had high depth, compared with 9% in Colombia programs and less than 5% in Bolivia programs. Moreover, there were substantial differences across programs within countries. In Peru, for example, fewer than 8% of the conditions in a social sector reform program were high-depth conditions, compared with almost 30% in the energy program. The most consistent differences appeared to be at the thematic level: almost a quarter of the conditions in programs in the financial and energy sectors were high-depth, compared with slightly above a tenth in the social and public sector and economic management clusters.

Programmatic PBLs in countries whose reform processes were further advanced at the outset tended to have higher depth conditions. For example, energy sector reforms in Surinam were only modestly advanced when IDB approved a programmatic PBL to help the country develop a framework for the energy sector. Most of the conditions consisted of one-off measures to help set building blocks, such as the preparation of diagnostic assessments and draft guidelines for future legal frameworks. In contrast, a programmatic PBL to support energy sector reforms in Nicaragua supported a reform process that was already advanced and in which the country already had experience. Although it had almost the same number of conditions as Suriname’s, Nicaragua’s PBL had a higher depth level, with conditions that included devising and implementing a new energy tariff structure.

Reforms supported at times of crisis were slightly deeper than those supported outside crisis periods. OVE examined whether PBL programs initiated in times of crisis (which tended to provide countercyclical funding) supported more ambitious reforms than programs started during less adverse economic times. When comparing the depth of the reform programs that were initiated during the global financial crisis (that is, programs for which the first loan was approved during 2008, 2009, or 2010) with those initiated either before or after, OVE found that, on average, programs initiated in times of crisis had slightly higher depth.

- 10For multitranche PBLs, the average number of conditions per loan was found to have increased from 23 to 32.