To explore what drives countries’ demand for PBL, OVE looked at four dimensions: (i) the frequency and intensity of PBL use; (ii) the correlation between PBL borrowing and growth rates, fiscal deficits, and gross financing requirements; (iii) countries’ reliance on parallel technical cooperation grants; and (iv) countries’ tendencies to fully complete or interrupt (“truncate”) programmatic PBL series. OVE analyzed these dimensions by reviewing all relevant lending documents and country economic data, carrying out an econometric analysis of lending, and interviewing IDB staff and officials from borrowing countries. Through this analysis, OVE identified four main categories of PBL users (Box 4.1).

- Mostly as budget support. This category included countries that resorted to PBL mainly in a countercyclical fashion (for example, to deal with a crisis that had suddenly halted capital inflows) or as a swift source of liquidity to handle short-term needs, such as debt servicing. In general, these countries exhibited a negative correlation between policy-based lending and GDP growth rates, and a positive correlation between policy-based lending and fiscal deficits or gross financing requirements. Their programmatic PBL series exhibited relatively high rates of interruption. They did not rely much on parallel IDB technical cooperation grants to accompany the reform programs. Since their demand for PBL depended on economic needs, these countries were not among the most regular users of PBL. In the decade leading up to 2015, examples in this category included Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Jamaica.

- Mostly as seal of approval for reforms and to benefit from IDB’s technical advice. This group comprised countries that tended to resort regularly to PBL and did so mostly to help legitimize their policy reform process by getting a “seal of approval” from IDB and to benefit from technical discussions between country officials and IDB specialists. Their PBL operations tended to be relatively small, and the demand for PBL tended not to be correlated with growth, fiscal deficits, or gross financing requirements. Moreover, programmatic PBL series in these countries had low truncation rates (a reflection of reform program implementation over a more extended time period and arguably higher ownership of the underlying reform program). They relied significantly on parallel technical cooperation grants provided by IDB to support the PBL programs. Peru and Bolivia were examples of this country grouping.

- Mixed. These countries sometimes relied on PBL to cover financing needs and sometimes used them to benefit from IDB’s validation and technical inputs. Examples in the decade leading up to 2015 included Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Panama.

- Preventive. Uruguay has used policy-based lending as part of the government’s precautionary borrowing strategy with multilateral development banks (MDBs). Since 2008, Uruguay has frequently postponed disbursements of approved PBL and used the proceeds only when it faced large financing needs. This practice was institutionalized with IDB’s introduction of the DDO modality in 2012. Recently, Uruguay resorted to drawing down resources from several DDO PBL operations to rapidly cover its financing needs to counter the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated social and economic effects.

Box 4.1. Rationale for Policy-Based Lending: Selected Cases

Jamaica and the need for budget support. More than half of Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) support for Jamaica in the decade leading up to 2015 was in the form of PBL, which helped the country advance public financial management and social reforms in the context of two IMF adjustment programs. Disbursements to Jamaica in 2010 in support of the first of those IMF programs (about $600 million) were among the largest IDB had provided to a borrowing country in a single year, both in per capita terms and as a share of GDP.

Peru’s regular use of PBL and IDB’s “seal of approval.” Peru stood out as the most regular user of PBL: it had 43 PBLs between 1990 and 2014, and 32 of them were approved in the decade leading up to 2015. Uniquely among IDB borrowers, Peru had at least one PBL approved every year between 2000 and 2015. The 32 PBL operations approved between 2005 and 2014 were arranged in 11 programmatic series. Most were long series (three or four loans each), supported by several technical cooperation grants, and all of them were completed—another feature that distinguishes Peru from many other IDB borrowers. However, each loan was relatively small. Peru used PBL to legitimize institutional reforms and obtain technical expertise through strong parallel technical cooperation grants, in a context of favorable fiscal results.

Colombia’s flexible use of programmatic PBL series. Colombia stood out for its heavy use of PBL, with 22 such operations approved between 1990 and 2014. Sixteen of these were approved between 2005 and 2014, accounting for more than half of the sovereign-guaranteed lending approved for the country over the period. The intensive use of PBL was the result of Colombia’s demand for funds to meet its annual fiscal and debt commitments, and to stimulate the economy when needed. This might help explain why Colombia’s programmatic PBL series were frequently interrupted. That said, Colombia also used PBL because it valued IDB’s technical support and it was a frequent user of parallel technical cooperation grants, which usually provided strategic inputs for the reform processes.

Panama’s recurrent shift in program focus. As in Peru and Colombia, IDB’s engagement with Panama pivoted on PBL: in the decade leading up to 2015, over 40% of all sovereign-guaranteed lending, and over 70% during the second half of the decade, was PBL. These operations were instrumental in providing policy advice to support Panama in building a strong macroeconomic policy framework, but PBL also became a regular (and reliable) source of government funding. As in Colombia, this might help explain why the programmatic PBL series in Panama were frequently interrupted. Successive changes in the focus of IDB’s programmatic lending prompted the truncation of most of Panama’s series in 2010–2014. As a consequence, five of 11 planned operations did not materialize, thus diminishing the relevance of the proposed lending series.

Support for subnational fiscal consolidation in Brazil. Until the early 2000s, Brazil hardly used PBL. Six of eight Brazilian PBL operations approved through 2014 were approved between 2012 and 2014. All of them supported reforms at the subnational level. Brazil’s use of PBL at the subnational level is unique among IDB borrowers.

Uruguay’s preventive use of PBL. Uruguay made use of a limited number of relatively large PBL operations as a liquidity management tool. Even before IDB introduced a deferred draw down option (DDO) in 2012, Uruguay opted to delay drawing down the proceeds of two PBL operations until December 2008 and January 2009, after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, when the external cost of financing in the market had substantially increased. Since the introduction of the DDO in 2012, Uruguay has made frequent use of this option.

DDO = deferred draw down option, IDB = Inter-American Development Bank, PBL = policy-based lending.

Source: Based on IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB. Document RE-485-6. Washington, DC: IDB.https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-design-and-use-policy-based-loans-idb

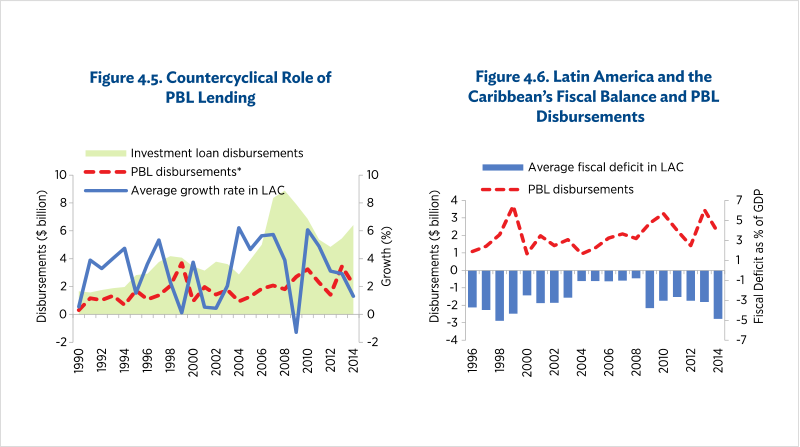

Overall, OVE concluded that, despite the range of reasons for using PBL across countries, the predominant use was for budget support in time of need. Its review found that, while countries valued the policy dialogue and technical expertise that came with IDB PBL, the policy elements were usually secondary to the primacy of budget support. Econometric analysis found that policy-based lending was negatively correlated with a country’s growth rate, and positively correlated with the size of fiscal deficits and gross financing needs (Figure 4.5, Figure 4.6). Drawing on the literature on early warning signals for economic and financial crises, OVE estimated fixed-effects panel regression models using PBL disbursements as a percentage of GDP as the dependent variable. The results confirmed that countries’ financing objectives were a key motivation for the use of PBL, both to handle short-term financing needs and to face contingent shocks. The use of PBL for budget support purposes was found to be particularly pertinent for small economies, which tended to be more vulnerable to external economic shocks and for which IDB financing could be decisive in helping them to weather a storm. While larger countries also made use of PBL for fiscal and liquidity management purposes, the instrument’s ability to affect macroeconomic conditions in these countries was limited by the small size of the loans in relation to their overall economies. While PBL played a major financing role, its countercyclical role overall was limited in most countries by the overall cap on PBL and the fact that PBL could not be disbursed if borrowers did not have a positive macroeconomic assessment.

An analysis of the extent to which PBL funding is complementary or a substitute for market financing was beyond the scope of OVE’s 2015 review and therefore remains an open question. OVE country program evaluations suggest that some countries with ample access to international financial markets tend to use PBL as a debt and liquidity management tool to complement market financing, particularly when borrowing during good economic times. A Colombia country program evaluation, for example, found that, as the country gained increased access to financial markets, PBL remained an attractive instrument because its large and predictable disbursements facilitated the Ministry of Finance’s financial planning, given that Colombia tended to issue bonds in January and September. Similarly, a recent evaluation of Mexico’s country program found that the Ministry of Finance sought regular and predictable disbursements for debt management purposes.9IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). 2015. Country Program Evaluation: Colombia 2011-2014. Washington, DC: IDB. https://publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-colombia-2011-2014; IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). 2019. Country Program Evaluation: Colombia 2015-2018. Washington, DC. IDB https://publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-colombia-2015-2018; IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). 2019. Country Program Evaluation: Mexico 2013-2018. Washington, DC. IDB https://publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-mexico-2013-2018

GDP = gross domestic product, LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean, PBL = policy-based lending.

Source: IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). Design and Use of Policy-Based Loans at the IDB. Document RE-485-6. Washington, DC: IDB.https://publications.iadb.org/en/ove-annual-report-2015-technical-note-…

- 9IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). 2015. Country Program Evaluation: Colombia 2011-2014. Washington, DC: IDB. https://publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-colombia-2011-2014; IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). 2019. Country Program Evaluation: Colombia 2015-2018. Washington, DC. IDB https://publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-colombia-2015-2018; IDB Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE). 2019. Country Program Evaluation: Mexico 2013-2018. Washington, DC. IDB https://publications.iadb.org/en/country-program-evaluation-mexico-2013-2018