James Melanson and Jason Cotton. The mandate of the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) is to reduce poverty and transform lives by contributing to the sustainable, resilient, and inclusive development of its Borrowing Member Countries (BMCs). PBOs are financing instruments—loans, grants, and guarantees—that are used to incentivize the implementation of country-owned policy reforms and institutional changes aimed at advancing sustainable development goals. PBL provides fast-disbursing budget support to finance priority expenditures while helping to strengthen the effectiveness of public policy frameworks. It is disbursed following compliance with agreed policy actions and supports the process of good policy making and governance while reducing transactions costs and providing timely resources to national budgets. PBL is complementary to investment lending, as it helps establish an enabling environment for enhancing resilience, achieving economic growth, and reducing poverty. It is an important CDB intervention modality to enhance development effectiveness and responsiveness to the changing needs of members.

CDB PBOs can take several forms:

- Macroeconomic PBOs address external or internal economic imbalances.

- Sector PBOs support reforms that help address critical sector issues and strengthen progress toward overall economic development.

- Exogenous shock response PBOs provide resources in crisis situations to assist with the fallout from a shock; they can support reforms to enhance resilience.

- Regional public goods PBOs help embed the policy and institutional frameworks necessary to advance regional cooperation and integration.

- PBO guarantees guarantee a portion of debt service on a borrowing or bond issue by a BMC in support of country-owned policy reforms.

PBL can be an important component of country financing strategies. At the country level, the size of the loan is related to development financing requirements, defined in terms of balance of payments, fiscal, sector, or other economic funding needs.

CDB began participating in PBL operations in the late 1980s, with operations to support macroeconomic adjustment executed in collaboration with the IMF, World Bank, and IDB. These operations addressed complex development problems, made more acute by the increased frequency of natural disasters and the impacts of climate change, external shocks, relatively low growth, and high debt in Latin American and Caribbean states.

In 2005, CDB formally introduced PBOs into its lending toolkit. Since then, it has sought to gradually strengthen the PBO instrument and the policy governing its use. Five external reviews or evaluations, as well as internal assessments by staff, have guided these efforts. Over time, they have revealed scope for improving the administration of PBOs, particularly in their design, supervision, and reporting, and the need to develop a more comprehensive and structured policy framework and guidelines. CDB has also experienced internal capacity building in results-based management, country fiscal diagnostics, and debt sustainability analysis.

In 2013, a significant revision to the 2005 framework was undertaken to provide greater clarity on the principles, procedures, and guidelines for administering PBOs and to anchor them within CDB’s overall risk management and control framework. The new framework provided for an increase in the PBL limit from 20 percent of total loans and guarantees outstanding to 30 percent and subsequently, subject to further approval, to 33 percent. It also introduced risk-based and policy-lending allocation limits (from a credit risk, use, concentration, and capital adequacy standpoint) at the country level that align with, and preserve, the prudential soundness of CDB. Following a comprehensive review of operations and the establishment of a centralized Office of Risk Management in May 2013, the PBL limit rose to 33 percent in December 2015.

In March 2020, CDB’s board approved an increase in the prudential limit to 38 percent, creating headroom for lending in response to the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. The increase is expected to be temporary, with a return to 33 percent by the end of 2023.

The PBL framework encourages collaboration with development partners when they have PBOs that pursue similar expected outcomes to those of CDB. CDB seeks to harmonize appraisal, supervision, and monitoring using a common policy matrix. When CDB resources will not be able to close the financing gap, staff either appraise a PBO request as part of a joint operation with other development partners or consult closely with strategic partners to help mobilize resources. Staff must assess the adequacy of the macroeconomic framework for the conduct of a PBO. The views of the IMF and the existence of an IMF program or an Article IV assessment are important ingredients in the appraisal. Absent an IMF program or Article IV assessment in the preceding 18 months, an assessment letter of the macroeconomic framework is requested. For overseas territories of the United Kingdom, a letter of approval from the requisite authority in the United Kingdom is sought.

Between 2005 and September 2020, CDB undertook 27 operations, amounting to $944.7 million. In 2019, PBL represented 42 percent of CDB’s total loan approvals and 54 percent of its loan disbursements. PBL has financed emergency priority spending and helped preserve stability in BMCs, which are highly vulnerable to external shocks and natural disasters. This vulnerability derives from inherent structural characteristics, such as lack of economies of scale or economic diversification, export concentration; remoteness from global markets; dependence on external financing; and exposure to natural hazards and climate change.41Caribbean countries are seven times more likely than other countries to be affected by a natural hazard and to suffer damage that is six times greater. See Sebastian Acevedo Mejia. 2016. “Gone with the Wind: Estimating Hurricane Climate Costs in the Caribbean.” IMF Working Paper WP/16/199. Washington, DC: IMF.

During 2006–2042Data for 2020 cover the months January–September,PBL activity correlated closely with periods of economic and natural hazard shocks. In 2008, on the heels of the global financial crisis, CDB approved nine PBOs, totaling about $340 million (36 percent of the PBL portfolio). Given the increasing frequency and intensity of hurricanes in the region, PBL demand has remained strong since 2015, peaking in the 2017 and 2019 hurricane seasons. Since the introduction of PBL, practice has evolved, reflecting CDB’s learning and experience in managing the instrument and its observation of experience at other MDBs.

The findings and conclusions of a 2017 evaluation conducted by CDB’s Office of Independent Evaluation, based on evidence from document review, case studies, and a wide range of interviews, suggests that several key factors increased the likelihood of PBL operations achieving their desired results. These included (a) clear objectives and results logic, with indicators and targets that can be measured and verified; (b) a selective focus on a manageable number of expected reform outcomes; (c) agreement on a small number of prior actions clearly linked to those outcomes; (d) good understanding of external risks and elaboration of mitigation strategies; (e) an engagement process with BMCs that engenders ownership and commitment by borrowers; (f) a menu of PBL options that offers the right instrument calibrated to borrowers’ reform readiness; (g) an understanding of national capacity constraints and, where needed, provision of affordable technical assistance to address them; (h) designation of an identified champion in the national public service with responsibility and authority for achieving reform results; and (i) consistent monitoring to identify when conditions are met, and the degree of progress toward reform outcomes.

Although the evaluation found that CDB’s PBL was increasingly taking these factors into account, it offered several recommendations to encourage further progress:

- CDB should review its practice of management for development results (MfDR) in the PBL program, making sure its design processes respect good MfDR practice, with clearly stated expected outcomes and indicators that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

- A corollary of more carefully stated results frameworks would be more tailored risk mitigation strategies. To date, such strategies have tended to be generic across PBOs. They should be more closely matched to the specific circumstances of the national context and reform program.

- CDB’s PBLs should focus on a small number of key outcomes, with prior actions that are causally linked to them. The choice of outcomes should take account of the limited size of CDB’s PBL loans, BMC priorities and CDB’s own country strategy, and an agreed longer-term reform program.

- This focus should be maintained over time, with prior actions in successive PBOs building incrementally on one another.

- National ownership and leadership are indispensable to the success of development reform programs. CDB should facilitate these to the greatest extent possible through collegial engagement with BMCs in PBL design and implementation. Doing so will require consultations with a sufficient breadth of national stakeholders, at both leadership and implementation levels, to gain commitment and follow through on reform objectives and prior actions. A good practice to be encouraged is the designation of a “champion” from the BMC’s public sector for implementation of targeted reforms. Small economies experience serious capacity constraints to implement reform programs. These constraints need to be anticipated and responded to as part of an effective PBL program. Relative to other MDBs, CDB has a more intimate understanding of the contexts and constraints of its BMCs, but it has carried out only limited needs analysis and there has been limited uptake of CDB technical assistance in connection with its PBL loans. CDB should investigate the reasons for this and make sure potential technical assistance requirements are well analyzed at the design stage and that flexibility is shown when such assistance is implemented.

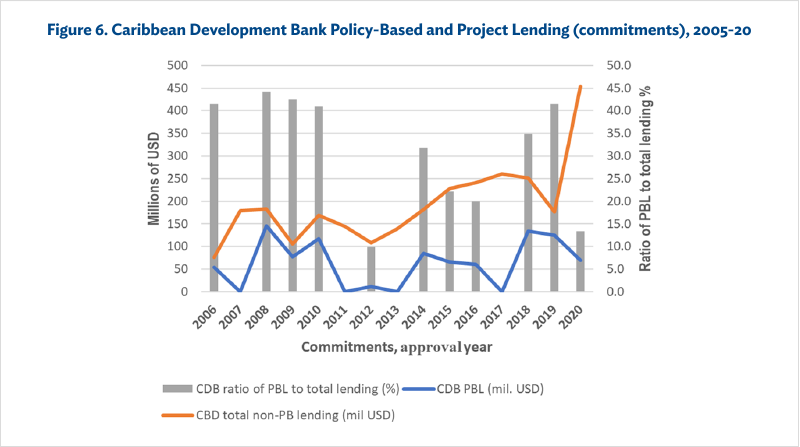

CDB’s policy-based and project lending (on commitment bases) for the period 2006–20 is shown in Figure 6. While non-PBO lending rose sharply in 2020, PBO lending fell and the ratio of policy-based lending to total lending fell well below CDB’s temporary cap of 38 percent. For CDB the lending pattern has become increasingly reflective of the financing needs arising from natural disasters than global events.

Note: PBL = policy-based lending

Source: Office of Independent Evaluation Office, the Caribbean Development Bank.

Comments by Ali Khadr

The chapter provides an informative overview of the findings of five assessments, including two Office of Independent Evaluation (OIE) evaluations of CDB PBOs. Among many other findings, it conveys how the institution’s practice of PBL, as well as the associated framework and guidance, has evolved over the roughly 15 years since it was initiated. Even with the favorable evolution of CDB’s PBL practice, there is room for further improvement.

Like other MDBs, CDB has moved over time toward the body of good practice identified in an ever-growing PBL literature. Among the key elements of this emerging body of good practice are (a) more frequent use of the more adaptable programmatic PBL instrument variant rather than the more rigid multi-tranche variant; (b) a focus on fewer, “deeper” 43The concept of depth, used in several evaluations of PBL, can be traced back to the measure of “structural depth” developed and applied in Independent Evaluation Office. 2007. Structural Conditionality in IMF-Supported Programs, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fundprior actions in PBOs; (c) use of results frameworks with a tighter logic linking a small number of prior actions to a manageable number of key outcomes sought, as well as associated use of specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) results indicators; (d) greater country ownership of proposed measures and outcomes sought, bolstered by broad prior consultation; (e) identification of capacity constraints to reform implementation and provision of parallel technical assistance as needed; and (f) identification and mitigation of risks adequately tailored to the specific operation. These elements raise questions about (a) the use of PBOs in small states and the shocks to which they are often subject; (b) the use of PBOs to strengthen fiscal management; (c) the analytical underpinnings of PBOs; (d) the quality of the results framework, including the depth of prior actions; and (e) establishment of attribution or contribution.

CDB is unique among MDBs in that its clients consist overwhelmingly of small states (formally defined as countries with fewer than 1.5 million inhabitants). Of the CDB’s 19 BMCs, 17 are small states (or dependencies), most of them islands or archipelagos.

As extensively documented in a burgeoning literature, small states as a group, especially small island states share several intrinsic characteristics and challenges. They include higher fixed costs (for instance, larger public expenditure, including public sector wage bills, as a share of GDP). The locations of these states also commonly entail high trade costs as well as extreme vulnerability to natural disasters and the deleterious effects of climate change. In addition, their exports tend to be very concentrated (usually in tourism and a few commodities), which makes them particularly vulnerable to trade shocks and contagion from trading partner downturns, including the downturn induced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

These intrinsic characteristics and challenges—particularly the exposure to repeated economic and natural shocks that are large relative to GDP—have resulted in a greater volatility of growth in small states compared with larger ones. Together with the inherent stresses on public finances and limited borrowing opportunities, these repeated shocks have often entailed fiscal distress and rapid debt accumulation, making effective fiscal and debt management imperative.

Given the shock-intensive country client context, PBL from MDBs has a clear role to play in CDB BMCs. It is especially encouraging to see that CDB has raised the prudential limit to 38 percent to create lending headroom to counter COVID-19-related fallout and offering exogenous shock response PBOs as a distinct instrument variant. Future evaluations of CDB PBOs can yield valuable lessons on how effectively such operations have supported small states, especially in helping mitigate the shocks to which they are subject and building resilience.

In many small states drawing on PBOs, fiscal management is likely to be—or at least should be—a central component. One area of focus in future PBL evaluation work by CDB could therefore be the quality of PBOs’ macro-fiscal frameworks, given recent findings in the evaluation literature to that it is positively associated with loan outcomes.

In an earlier study, the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) of the World Bank Group examined the quality of macro-fiscal frameworks in 390 World Bank PBOs completed during fiscal years 2005–13. It found that certain aspects of the quality of PBO macro-fiscal framework design were positively correlated with loan outcome ratings. Two aspects of the quality of the PBO framework showed a statistically significant association with loan outcome ratings: the credibility of the PBO framework given the country’s fiscal record and adequate coverage of quasi-fiscal risks (risks the government might need to devote public spending to off-budget items, such as an underfunded public pension system or state-owned enterprises in distress).

There is emerging, although not conclusive, evidence that strong analytical foundations can be an important determinant of PBO effectiveness. IEG found generally solid links between World Bank PBL design and integrative analytical work on public expenditure, as well as continuity in policy dialogue from the latter to the former. However, it was difficult to establish a clear association between such links and PBO outcome ratings, although PBOs informed by analytical work on public expenditures showed slightly better outcome ratings over 2009–12.

The depth of prior actions in CDB PBOs increased over time. Depth—the extent to which the reform measure on its own can bring about lasting change in the institutional and policy environment—is a key ingredient in the quality of the results framework. Noncritical, shallow, and process-related measures should be avoided.

A common complaint in PBL evaluations concerns the difficulty of attributing medium-term country outcomes to the use of PBOs, including the prior actions they support and the financing they provide. The difficulty is compounded when several development partners deliver PBL simultaneously. It is therefore not surprising to read in the chapter that “it was not feasible for the evaluation to gather a sufficient amount of directly attributable evidence to support statements of causal linkage between CDB’s PBL support and higher-level medium-term outcomes.” 44Chapter 5 in this volume.

Given the concentration of CDB clients in small states, CDB PBL evaluation work can yield valuable lessons about how CDB PBOs support small states in dealing with shocks, particularly whether PBOs adequately cover the multiple drivers of fiscal and debt sustainability and foster systemic, rather than incremental, changes in disaster and climate resilience by targeting incentives and behaviors. Other issues on which future CDB evaluation work could usefully focus include the quality of CDB PBOs’ macro-fiscal frameworks and analytical underpinnings, the quality of PBO results frameworks (including depth of prior actions supported), and establishment of the plausible likelihood of PBOs contributing to country outcomes.

- 41Caribbean countries are seven times more likely than other countries to be affected by a natural hazard and to suffer damage that is six times greater. See Sebastian Acevedo Mejia. 2016. “Gone with the Wind: Estimating Hurricane Climate Costs in the Caribbean.” IMF Working Paper WP/16/199. Washington, DC: IMF.

- 42Data for 2020 cover the months January–September

- 43The concept of depth, used in several evaluations of PBL, can be traced back to the measure of “structural depth” developed and applied in Independent Evaluation Office. 2007. Structural Conditionality in IMF-Supported Programs, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund

- 44Chapter 5 in this volume.