Monika Huppi and Gunnar Gotz. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) offers three broad lending categories among its sovereign-guaranteed loans: investment lending, policy-based lending (PBL), and lending for financial emergencies during macroeconomic crisis (called special development lending). PBL provides fast-disbursing financial assistance or country budget support conditional on the borrowing country fulfilling a set of agreed upon policy and institutional reforms. Investment lending disburses against specific predefined project expenditures. Special development lending also provides fast-disbursing support but is conditional on a country having been struck by a macroeconomic crisis, being supported by an active International Monetary Fund (IMF) program, and the special development lending being part of an international support package.

IDB introduced PBL in 1989, in response to the Latin American and Caribbean debt crisis. The instrument has evolved over time, leading to a decoupling from IMF support, the introduction of a programmatic variant and of a deferred draw-down option. The programmatic version consists of a series of single tranche operations set in a medium-term framework of reforms. The first operation identifies the policy conditions for the disbursement of that operation as well as indicative triggers for the subsequent loans in the series. Since the triggers can be revisited at the time of loan approval, programmatic PBL allows for conditions to be adjusted as circumstances change.

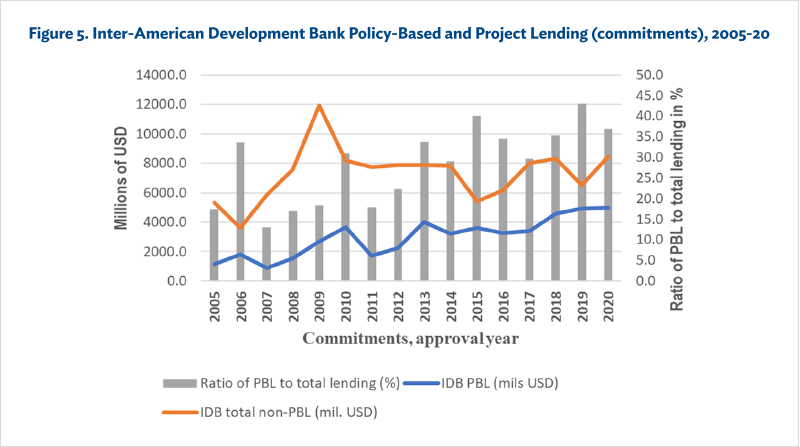

PBL has historically been subject to a lending limit which has changed over the years. In 2005–19, PBL accounted for about 28 percent of IDB’s sovereign-guaranteed approvals and amounted to $42.6 billion. About 80 percent of these resources were approved as programmatic operations supporting 124 programs, with the remaining 20 percent as individual single- or multi-tranche policy-based operations. All IDB borrowing member countries except one used PBL to varying degrees in the period. IDB’s PBL is rarely co-financed by other institutions and IDB tends to support reform processes in areas in which it has accumulated experience and knowledge. Emergency budget support has been provided through separate budget support instruments (currently called special development lending) that have also evolved. This form of support accounted for only 2 percent of sovereign-guaranteed approvals in 2005–19. During the first half of 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, policy-based and special development lending have spiked.

IDB’s Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE) has looked at PBL in several contexts, but a full-fledged evaluation of IDB’s PBL has yet to be undertaken. OVE routinely reviews the performance of PBL in its country program evaluations. It also reviews and validates IDB’s self-evaluations of completed programs and operations and assigns a performance rating to each completed PBL program or freestanding PBL operation. In addition, OVE undertook a thorough review of the design and use of PBL in 2015, which is summarized in the chapter.

The OVE review of the design and use of PBL found that although countries used PBL for various reasons, the predominant use was for budget support in time of need. While countries valued the policy dialogue and technical expertise that came with IDB PBL, the policy elements were usually secondary to the primacy of budget support. Although PBL provided important financial support, its ability to play a countercyclical role overall was limited because of the cap on PBL, the limited size of PBL operations compared to the economy in all but small countries, and because PBL could not be disbursed if borrowers did not have a positive macroeconomic assessment.

The extent to which PBL is complementary to or a substitute for market financing has not been systematically assessed by OVE’s review. In some instances, OVE’s country program evaluations show that countries with ample access to financial markets used PBL as a liquidity management tool to complement market financing and fill short-term liquidity needs, particularly outside an economic crisis.

In its 2015 review, OVE assessed the depth of the policy measurers supported by PBL and found that while they were generally relevant to the objectives of the reform programs they aimed to support, most policy conditions did not have enough depth to set in motion reforms that could by themselves bring lasting changes. Policy conditions were of higher depth in programs in the financial and energy sectors and during times of crisis.

Programmatic policy-based loans were found to allow for more sustained engagement. To the extent that policy measures became deeper as a programmatic series progressed, they were a useful tool to support reform programs while also helping borrowers meet financing needs. However, over one-third of programmatic PBL series active between 2005–19 were truncated before they reached their most consequential reform steps, raising questions about the ownership of the underlying reform programs that such lending sought to support. Truncation was more pronounced for PBL series in countries that resorted mostly to PBL to meet financing needs and did not seek technical assistance to accompany the underlying reform programs. That programs supported by technical cooperation grants had a lower truncation rate suggests the need for continuous engagement and technical cooperation to support borrowing countries in their reform efforts.

The findings of OVE’s work undertaken so far invite questions. To what extent does PBL complement or substitute for funding from financial markets? Are IDB-supported policy measures complementary to, or do they overlap with those of other institutions providing budget support? What nonfinancial additionality does PBL provide? What results have PBL operations helped achieve and how sustainable will those results prove to be? OVE plans to undertake a full-fledged evaluation of PBL at IDB to try to answer some of these questions.

IDB’s policy-based and project lending (on commitment bases) for the period 2005–20 is shown in Figure 5. Both PBO and non-PBO lending increased in 2020, though the ratio of policy-based lending to total lending fell slightly below IDB’s 40 percent cap.

Note: PBL = policy-based lending

Source: Office of Evaluation and Oversight, Inter-American Development Bank.

Comments by Augusto de la Torre

The chapter is divided into two sections. The first neatly summarizes the evolution of PBL and its use by borrowing countries since its introduction at IDB in 1989. The second assesses PBL along several dimensions (based on well-focused findings), including the reasons countries demand PBL, complementarities between PBL and other IDB operations, and issues in design and implementation of PBL operations. The analysis part of the chapter is strong when it comes to findings; it falls short when interpreting the implications of such findings for IDB and borrowing countries. The observations of this commentator elaborate on these questions and issues and raise a few others.

The chapter provides significant evidence that borrowing countries’ predominant use of PBL was to fill their budget financing needs, with policy elements usually being secondary to the primacy of budget support. This suggests that MDBs recognize that financing needs are at the heart of the demand for PBL but point to policies and reforms as a key reason for offering PBL. Efforts to align these two motivations drive PBL preparation and design. These efforts succeed at times but not always.

Not surprisingly, using a creative analytical approach, the OVE review found that most conditions in PBL were of low to medium depth. They tended to involve one-off and often reversible policy measures, to be process oriented, or to have good policy intentions that could not be implemented at the time. by themselves effect lasting change. The OVE review stressed that conditionality in PBL was generally relevant to the programs’ objectives but probably insufficient to attain the expected outcomes. The commentator concludes that the findings of the OVE report should lead MDBs to adjust expectations toward more realistic levels. PBL operations do not simply “buy” reforms, as is often believed. At best, they provide needed budgetary financing while recognizing—and helping fine-tune and strengthen the technical aspects of—reforms that would have been attempted by the country with or without the PBL.

Still, the commentator finds that the rise in programmatic policy-based loans (PBPs) can be interpreted as a major step toward greater realism and frankness in PBL. PBPs have accounted for the lion’s share of IDB-originated PBL since 2005. He concludes that wisely, PBPs do not pretend to “buy reforms.” Instead, each single tranche loan in the program recognizes and gives credit to the country for policy actions and reforms that have happened before loan disbursement. Future reforms appear only as indicative guides for future operations under the multiyear program.

As a result, PBPs avoid the time-inconsistency trap of traditional multi-tranche PBL operations, in which countries under duress may agree to conditions (reforms) with a low probability of being met (because the incentives to stick to the conditions diminish after the PBL is approved and the first disbursement comes in).

Related to the question of ownership is the crucial question of whether PBL or PBPs can realistically be expected to generate policy additionality. Given the difficulties in identifying a counterfactual, it is difficult to attribute policy reforms to PBL or, equivalently, to reject the hypothesis that those policy reforms would have taken place even absent PBL. This calls for modesty by MDBs, whose role is not so much to tell countries what to do but to partner with countries in their quest for social and economic progress, including in design, implementation, and evaluation of reform.

To mitigate the risks of low-depth reforms and truncation, a premium must be put on a continued and robust technical engagement and policy dialogue between the MDB and the country client. Doing so is particularly important considering several important findings in the OVE evaluation, including that “IDB tends to support policy reforms in sectors in which it had previously worked (usually through technical cooperation grants and investment loans) and thus has some country-level expertise that allows it to sustain a policy dialogue and provide relevant technical advice” and that “there was a significant positive relationship between technical cooperation support and the likelihood of a PBP series being completed.” 40Chapter 4 in this volume.This point also argues for not evaluating PBL—or any particular financial product offered by an MDB—in isolation, but in context—that is, considering the entire portfolio of services the MDB offers to its country clients, including financial services, knowledge services, and convening services.

The findings in the chapter raise questions about the complementarity and substitutability of PBL and market-based finance, an issue the chapter does not address but should. One hypothesis is that in countries with strong macro-financial policy frameworks, PBL is complementary to market-based finance—that is, these countries use PBL as part of their prudent management of the portfolio of public sector liabilities. In countries with weaker macro-financial policy frameworks, the hypothesis would imply that PBL is a substitute for market-based finance—that is, these countries resort to PBL because they lack access to market-based finance. The chapter should have explored this hypothesis and elaborated on the implications of what it found.

- 40Chapter 4 in this volume.