Karolyn Thunnissen. The European Commission first introduced budget support in the 1990s. The approach evolved in the context of conditionality reform and in response to the evolution of the aid effectiveness agenda. The current approach has been implemented since the beginning of the 2000s. The period was marked by a gradual shift from using only project aid, whose effectiveness was often undermined by weak policy and governance contexts. The form in which EU budget support was implemented evolved to reflect changing policy contexts and to act on recommendations by external evaluations and by the European Court of Auditors.

Unlike projects, budget support addresses the partner country’s overall conditions for economic and social development. EU budget support has always been provided exclusively as grants. It is consistent with and complementary to other EU aid implementation modalities, including projects, technical assistance, delegated cooperation, cofinancing, blending, and guarantees for investment loans by financial institutions, humanitarian aid, and emergency assistance.

The latest EU budget support policy was adopted in 2012. Its guidelines were revised in 2017 to take into account the new European Consensus on Development that followed the international adoption of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda. This policy notably introduced a new type of budget support, known as State and Resilience-Building Contract, to help countries in situations of fragility or facing the consequences of crisis and natural disasters. This type of budget support has increasingly been used and has proved instrumental in supporting countries during the COVID-19 pandemic lately.36European Commission. 2017. Budget Support Guidelines. Brussels https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/budget-support-guidelines-2017_en.pdf.

The EU’s approach to budget support has always involved four interrelated components acting together in support of partner countries’ policy implementation:

- policy dialogue with a partner country to reach agreement on the policies and reforms to which budget support can contribute

- performance assessment to achieve consensus on expected results and to measure progress achieved

- financial transfers to the treasury account of the partner country once those results have been achieved and according to their degree of achievement

- capacity development to enable countries to implement reforms successfully and to sustain results.

EU budget support is thus a performance-based modality that provides a package of grant funding, capacity development, and a platform for dialogue to partner countries in support of the implementation of their policies. Funding is fungible: Budget support is used by the partner country’s government based on domestic budgetary planning, execution, and oversight processes and using domestic PFM systems. EU budget support grants can thus be used for both recurrent and investment expenditure.

Policy dialogue is a fundamental component of EU budget support. The general conditions (regarding public policy, macroeconomic stability, PFM, and since 2012, budget transparency and oversight) provide the overall framework for dialogue with the government and other stakeholders; variable tranche indicators enable a more in-depth discussion on key reforms and policy results. Because funds are transferred to the budget, the EU can discuss general PFM issues, overall budget allocations, and sector spending as well as its results with the partner countries’ authorities and other stakeholders. Because of the grant nature of the funding, the EU is particularly concerned that budget support should not be considered a substitute for efforts to raise revenues. Domestic resource mobilization is systematically raised in policy dialogue and often supported through capacity strengthening or the use of performance indicators. Monitoring of general policy outcomes and sector-level policy processes, activities, outputs, and most important, outcomes are an essential input into the overall dialogue.

Although external experts hired for technical cooperation can never be responsible for achieving the targets set for the agreed performance indicators, the capacity building most often associated with budget support is used to enhance the government’s capacity to design, implement, monitor, and evaluate policies and to deliver public services. As EU budget support relies on the monitoring of performance indicators, preferably outcome indicators, the strengthening of national monitoring frameworks and associated statistical systems is a priority. Attention is also systematically paid to promoting the active engagement of nongovernment stakeholders in these monitoring frameworks.

Independent evaluation teams have undertaken 17 general and sector budget support evaluations applying the universally accepted OECD-DAC methodology for budget support evaluations (the so-called “three-step approach”) since 2010.37Independent evaluations of budget support using only steps 1 and 2 of the OECD-DAC methodology are more systematically undertaken at program level. See OECD. 2012. Evaluating Budget Support, Paris.They were managed by evaluation management groups made up of representatives of partner countries and funding agencies, under Commission’s coordination. Of the 17 evaluations undertaken, 11 were multidonor evaluations assessing the joint effects of all the general and sector budget support operations financed by different development partners. Evaluation periods differed slightly across the evaluations, which stretched from 1996 to 2018.

The period being evaluated (roughly 2005–2015, although seven of the eight evaluations concentrated on 2005–10) was a period of high and increasing official development assistance (ODA), with budget support the preferred aid modality of the EU and multilateral development partners. Budget support provided a significant and predictable source of funding for recipient governments and created fiscal space for them to undertake discretionary expenditure. The scale of budget support in relation to public expenditure was significant in all countries. Budget support annual disbursements represented as much as 25 percent of public expenditure in Uganda in the first half of the period; 15 percent of public expenditure in Burkina Faso; over 10 percent in Mali, Mozambique, and Tanzania; 8 percent in Ghana; and 6.5 percent in Zambia. Even in Tunisia, where it represented only 1.4 percent of public expenditure, budget support was an important source of funding for discretionary expenditure.

The predictability of the amounts of budget support was high, with disbursements close to planned amounts in most cases, even though failure to meet eligibility conditions triggered temporary suspensions of budget support by the EU and other development partners in five of the eight countries during the evaluation period. In three cases, temporary suspension was linked to the government’s breach of principles (major corruption and fraud cases came to light in Tanzania in 2007 and 2008; Zambia in 2009; and Mozambique in 2009, 2011, and 2012). The EU’s general budget support was not yet explicitly linked to respect for fundamental values but only to the eligibility criteria, which continued to be satisfied. While corrective measures were discussed and then implemented, the EU continued to disburse funds, which eased the effect of these suspensions on the government’s treasury tensions. In two other cases, Uganda (2012) and Ghana (2013 and 2014), underperformance on results, a deteriorating macroeconomic situation, and serious concerns regarding PFM triggered all development partners, including the EU, to suspend budget support, because the key conditions were no longer being met.

With these temporary suspensions and deferred disbursements of budget support because of countries’ breach of mutual accountability, the predictability of disbursement timing could not be maintained. In Mali, Uganda, and Zambia, public expenditure was delayed and the government had to seek temporary domestic borrowing.

In most EU budget support operations, capacity development complements funding, policy dialogue, and performance monitoring. Technical assistance is used to strengthen the country’s policy and PFM systems, improve the accountability of the government toward its citizens, and strengthen key institutions and policy making processes. Typical areas of support include external oversight; monitoring and evaluation; underlying statistical data systems and processes; PFM, including gender budgeting and monitoring; and the active engagement of stakeholders in policy design, implementation, and monitoring.

Technical assistance usefully complemented budget support in backing governance reforms and reinforcing capacities in PFM, audit, and statistics in six of the eight countries. Where sector budget support was provided alongside general budget support, sector capacities also benefited from technical assistance. In Ghana, major efforts were made to strengthen the capacities of civil society organizations and to enhance their role in policy processes. Overall, technical assistance remained a minor component of the budget support package; in many instances, evaluators estimated that more could have been done with better planning and a more flexible response to strengthen capacities at the subnational level, where policy implementation takes place.

In every result identified in all eight evaluations as a direct or indirect effect of budget support, policy dialogue featured as a central element. Dialogue related to budget support was invariably a crucial factor in improving policies, governance, and policy decision making. Through their policy dialogue, development partners were able to put and keep specific issues on the government’s priority agenda, draw attention to governance matters, and propose and discuss policy options. Development partners also used performance monitoring and the variable tranche indicators to discuss results of policy implementation, corrective measures, and implementation challenges.

Strong coordination of budget support donors within a structured framework increased the effectiveness of policy dialogue, facilitating harmonization, alignment, and the delivery of joint messages. During the period, temporary suspensions of budget support disbursements led to a severe deterioration of relations between the government and development partners in several countries. The overall positive assessment of budget support policy dialogue was tempered in several cases by a perceived lack of government ownership and leadership of the policy dialogue as well as by extending budget support areas of interest to ever wider governance and sector issues for which reform capacities were insufficient.

General budget support was found to have induced and sometimes helped to trigger positive and mostly lasting changes in four main areas: policy formulation and implementation, the composition of public spending, PFM, and transparency and external oversight. Also, general budget support accompanied improvement in policies in several areas, depending on the objectives pursued and the weaknesses to be addressed.

Improvements in sector policies and delivery processes were substantial when general budget support was paired with sector budget support. In several countries, budget support contributed to strengthening of sector policies, adoption of a sector-wide approach, and implementing sector policies.

Discretionary funding enabled by budget support helped governments to significantly increase their social and pro-poor expenditure, in particular in the low-income countries (LICs), which led to expanded access and delivery of services in these priority sectors. The gains in social outcomes were momentous, but not always equitable. PFM, supported by policy dialogue, technical assistance, and the monitoring of PFM performance indicators, also improved in all countries except one as shown by repeated Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability reports. Evidence of strengthened transparency and external oversight as well as sector governance was also found in most countries receiving budget support. However, in fragile countries, where budget support contributed to fiscal stabilization and strengthening the capacities of vital state institutions, the strengthening of the institutions responsible for security, justice, peace, and democratic governance has been slower than expected.

The evaluation findings summarized here should be considered in their context. This synthesis was based on evaluations undertaken in 2011–20 of budget support programs implemented during 1996–2018. Looking across the 17 evaluations and with the benefit of hindsight, some of the progress to which budget support contributed was short-lived, especially when countries experienced drastic sociopolitical, economic, or security shocks. The risk of losing progress never disappears; it therefore needs to be monitored closely during budget support implementation. This finding may also indicate the need for deeper consideration of the factors that would help ensure the sustainability of outputs and induced outputs when designing budget support and evaluating its effectiveness.

Each of the 17 evaluations made recommendations to improve the use of budget support in the country concerned and, sometimes, to improve the specific programs, policies, and institutions supported. Recommendations that were less context-specific and could be applied to the management and use of budget support included: (a) establish new types of partnerships with partner countries, using cooperation modalities and tools differently; (b) use budget support as a complement to other aid modalities; (c) strengthen policy dialogue; (d) carefully consider the choice and use of performance indicators for the variable tranches; (e) improve technical assistance.

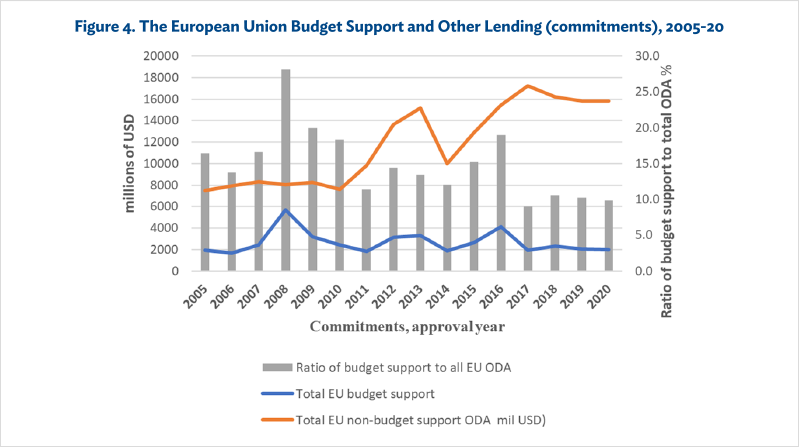

EU’s policy-based and project lending (on commitment bases) for 2005–20 is shown in Figure 4. Although non-PBO lending remained at high level in 2019–20, PBOs were not countercyclical as they had been during the previous crisis.

Note: ODA = official development assistance

Source: European Union.

Comments by Shanta Devarajan

This chapter is a useful description of the European Union’s budget support instrument and synthesis of the 17 independent evaluations of budget support operations. The EU’s budget support programs have many distinctive aspects, some of which the chapter highlight. The synthesis of the evaluations paints a generally favorable view of EU budget support, although without a counterfactual analysis of the true impact cannot be discerned.

The two main distinguishing characteristics of EU budget support are that it is provided exclusively as grants rather than loans and is disbursed based on observable and monitorable indicators of performance, such as progress in implementing PFM reforms. EU budget support differs from budget support operations of the World Bank or AfDB, which mainly provide loans (some of which are concessional) and disburse based on prior policy actions rather than results.

The fact that the EU provides grants has implications for the definition of the appropriate macroeconomic framework. While everyone agrees that budget support should be provided only in a stable macroeconomic environment (hence the EU’s collaboration with the IMF), the definition of “a stable macroeconomic environment” may be somewhat different if the country does not have to repay a loan. Hence, the macroeconomic framework for EU budget support may not necessarily be the same as the frameworks of the IMF or World Bank.

Disbursement of EU budget support is based on progress in meeting certain benchmarks agreed upon at the beginning of the program. The disbursement is made of a fixed component (which requires general conditions to be met and whose amount do not vary) and a variable component, which serves as a performance top-up and is disbursed proportionally to a set of additional and specific performance indicators (provided the general conditions are met). The disbursement can therefore be full (fixed tranche and the totality of the variable tranche), partial (fixed tranche and part of variable tranche, if progress was only partial), or nil (one of the general conditions is not met). This system of disbursement contrasts with the approach taken by the MDBs, whose budget support is disbursed based on policies undertaken (prior actions) rather than on results. To the extent that there is a difference between ex ante policies and ex post performance, one wonders how countries can coordinate across their budget support donors.

Performance-based conditionality (PBC) raises three issues of its own. First, because development is a risky business—whether a given policy reform will yield the expected outcome is not known—PBC puts more of the risk on the recipient.

Second, other attempts at PBC, such as the World Bank’s Program-for-Results (PforR) financing, have found a tendency to “dilute” the performance criteria (in order not to risk failing to disburse) to the point where they resemble ex ante policy conditions.38Alan Gelb, Anna Diofasi, and Hannah Postel. 2016. “Program for Results: The First 35 Operations.” CGD Working Paper, 430. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.The reality is that both the donor and the recipient have an interest in seeing the operation disburse and therefore may, even subconsciously, nudge conditions in that direction. It is possible that this is happening with EU budget support as well.

Third, the chapter notes approvingly, in addition to budget support, the EU provides technical assistance to countries to further progress on key areas such as PFM. Although it is desirable that EU technical assistance, budget support conditions, and policy dialogue all pull in the same direction, there may also be problems here. If the EU is providing technical assistance in an area that is also a performance criterion for tranche release, at least two things could happen. If the country fails to meet the performance criterion, it could blame it on the technical assistance, or the organization providing the assistance could try to influence the EU into certifying that the country had met the criterion, lest its own performance be judged as mediocre. Even if the technical assistance and budget support operation are kept independent, as both being provided by the same institution, it is difficult for the country to not perceive them as linked.

The independent evaluations synthesized in the chapter all follow the same three-step framework. First, the effects of the budget support operation on policies and institutions are analyzed. Second, the outcomes and outputs in a country are related to policy and institutional changes. Third, the results of the first two steps are combined to provide a narrative of how the budget support operation, through its contribution to policy and institutional change, helped achieve outcomes and impacts.

There is an attempt to specify a counterfactual in some of the individual steps, but the overall narrative does not include one. One way of constructing a counterfactual is to compare one country with another with similar characteristics that did not receive a budget support operation from the EU. This cross-country analysis has been used in other evaluations of budget support operations.39William Easterly. 2003. “IMF and World Bank Structural Adjustment Programs and Poverty.” In Managing Currency Crises in Emerging Markets, ed. Michael P. Dooley and Jeffrey A. Frankel. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Another is to compare the same country’s performance in two periods, one in which there was a budget support operation and one in which there was not. Such an analysis would need to adjust for other factors, such as a terms-of-trade shock, that may have affected the economy during the budget support phase but were unrelated to the operation. If, for instance, a country experienced a favorable terms-of-trade shock during the period of the operation, the success of the operation may have been because of the shock rather than the operation.

The value of having a counterfactual goes beyond just having a better estimate of the project’s impact. It also helps disentangle the different components of budget support. As the synthesis notes, budget support operations have three components: the transfer of resources, technical assistance, and dialogue on policy reforms aimed at achieving the targets of the operation. What is the relative importance of each?

The chapter notes that many evaluations discussed the relative contributions of the financial transfer (flow of funds), technical assistance, and policy dialogue, but this seems to be based on the relative magnitude of the financial transfer and the intensity of technical assistance and policy dialogue rather than on a model of the combined effect of the three on outcomes. Nevertheless, the chapter finds that the flow of funds played a greater role in the general budget support operations than in sector budget support. The reason could be that the sector budget support operations were concentrated in MICs, including some upper-middle-income countries; the financial transfer represented a tiny part of the government’s budget (0.6 percent as opposed to 15 percent for general budget support). In addition to their relative contributions, one needs to understand the interaction between financial and knowledge assistance.

The bundling of finance and policy dialogue into budget support raises the broader question of why they should be bundled. If these policy reforms benefit the country, why do they not implement them anyway? Why is it necessary to incentivize them with funding?

One answer is that the financial transfer acts as an encouragement for the government to undertake the reforms, suggesting that the reforms are not collectively owned by the whole of government. The financial transfer helps fix a fundamental political economy problem in the country (usually on a temporary basis). It is not clear that such solutions are sustainable. It is also not clear that external actors, such as the European Union or World Bank, can or should select reform champions in the country.

The financial transfer associated with budget support can have two other effects that may not be conducive to better development outcomes. The synthesis in the chapter hints at some of them but does not develop their implications. The first is the fungibility of aid resources, which the chapter mentions. As the financial transfer goes directly to the government’s budget, it could in principle be used for any expenditure. Several evaluations speak favorably of the fact that pro-poor expenditures—on, for example, health, education, and social protection—rose during a budget support operation. But if the country was planning on increasing spending in these sectors anyway, then the EU’s funds were being used to finance other expenditures, about which little is known. This possibility is not just theoretical. There is evidence on the fungibility of aid in general. The second problem with the financial transfer links back to the political economy problem mentioned earlier.

Most of the evaluations seem to equate increased public spending on health and education with improved health and education outcomes. Evidence for this link is weak at best because the delivery of basic services in health and education is poorly targeted and often ineffective (often because of absentee teachers or doctors). The chapter notes this discrepancy by pointing out that the gains were momentous but not always equitable… and gains in access have not always been accompanied by better quality of services.

- 36European Commission. 2017. Budget Support Guidelines. Brussels https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/budget-support-guidelines-2017_en.pdf.

- 37Independent evaluations of budget support using only steps 1 and 2 of the OECD-DAC methodology are more systematically undertaken at program level. See OECD. 2012. Evaluating Budget Support, Paris.

- 38Alan Gelb, Anna Diofasi, and Hannah Postel. 2016. “Program for Results: The First 35 Operations.” CGD Working Paper, 430. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

- 39William Easterly. 2003. “IMF and World Bank Structural Adjustment Programs and Poverty.” In Managing Currency Crises in Emerging Markets, ed. Michael P. Dooley and Jeffrey A. Frankel. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.