The Independent Evaluation Department (IED) of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) evaluated the use of policy-based lending (PBL) by ADB between 2008 and 2017. The design and reform focus of ADB PBL fundamentally changed over this period, and the success rates—as judged by project completion reports validated by IED—more than doubled (from about 33 percent to over 80 percent), a trend also experienced by other multilateral development banks (MDBs). Improved performance appears to have coincided with the growing use of single tranche PBL and, with it, the use of prior actions (actions completed before loan approval). These changes substantially reduced disbursement risks and increased the capacity of MDBs to provide more predictable and reliable budget support in response to country financing needs, the primary objective of the instrument.

A key issue is whether the need to respond efficiently to country financing needs has encouraged support for less critical reforms. Over time, PBL reform topics seem to have shifted from more politically sensitive reforms (such as reform of state-owned banks) to more technical reforms connected with public financial management (PFM). PBL modalities also changed as the second tranches of loans, which often contained more difficult policy actions, were no longer part of PBL design. The policy actions in second tranches often required waivers or loan cancellations contributing to poor performance ratings. There appears to have been a trade-off between the emphasis on efficient, rapidly disbursing modalities to meet country financing needs and the emphasis on policy reform, suggesting that the two objectives are not always automatically compatible.

PBL performance dramatically improved over the evaluation period, but the evaluation identified several design issues. For example, PBL tended to be used in the region’s more developed economies (Pakistan is an exception) with greater capacity for reform. It rarely focused on policy reform in areas of infrastructure development, ADB’s main comparative advantage. Moreover, it was difficult to reconcile the high success rates in PBL project completion reports validated by IED with the evaluation’s finding of design shortcomings. A key reason for this discrepancy is that although PBL performance significantly improved over the evaluation period, the causal chain from policy actions to country-level results was often difficult to discern. Where there is doubt about whether a PBL outcome resulted directly from the policy actions taken, the responsibility often falls on the evaluator to prove the connection by, for example, constructing a counterfactual to show whether the result would have been achieved without the PBL. In practice, however, if outcome indicators are achieved, the PBL is usually rated successful even if causality between ADB-supported policy actions and the reform outcome is tenuous.

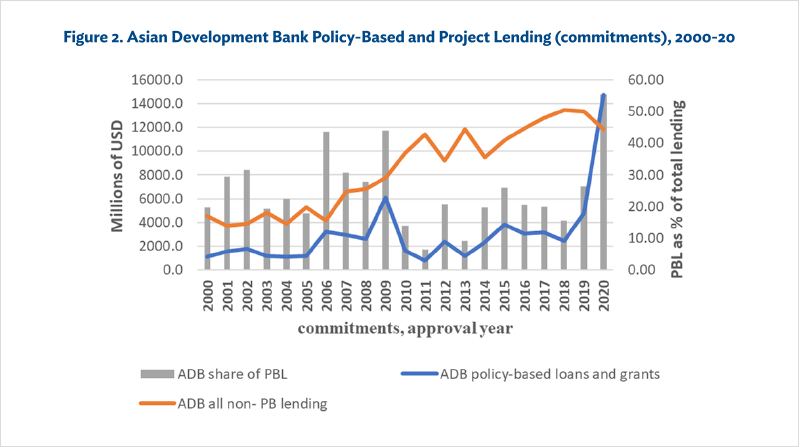

PBL remains an efficient modality for supporting country clients through crisis periods. Its usefulness was shown by ADB’s rapid response to the global economic and financial crisis in 2007–09 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The use of PBL spiked during crisis years, breaking through the 20 percent ceiling imposed on this type of lending in the sovereign loan portfolio. The increase in PBL use beyond the ceiling was made possible only through the introduction of “reform-free” and rapidly disbursing budget support modalities to finance developing member countries’ (DMC) countercyclical public expenditure programs to mitigate the effects of the crisis.

PBL has played several roles in the region. It supported countries through difficult periods, including economic downturns, natural disasters, and pandemics, and it supported broad public sector management and macroeconomic stability through noncrisis years. Other budget support mechanisms are also emerging, including results-based lending, which is more effective than PBL at directly improving service delivery.

The evaluation published in 2018 made several recommendations, some strategic and others related to PBL design. At the strategic level, it recommended ADB make greater use of PBL to support policy reforms in sectors where significant project investments are also undertaken, to forge more integrated and sustainable solutions to public policy problems in these areas. Although ADB management accepted this recommendation, it is unlikely to be implemented in the short term, mainly because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to higher use of non-reform-based budget support responses in 2020. If such support continues, the opportunity to use PBL to support infrastructure-related policy reform is likely to be limited in the immediate term.

The evaluation’s recommendation that ADB develop an operational plan on the scope, objectives, and articulation of public sector management interventions was not accepted formally, but ADB has moved in this direction. An operational priority plan for governance and institutional capacity has since been developed as part of ADB’s Strategy 2030. This plan provides corporate guidance on the conditions under which PFM loans should be provided.31Asian Development Bank. 2019. Strategy 2030. Operational Plan for Priority 6. Strengthening Governance and Institutional Capacity 2019–2014. Manila.

The evaluation recommendations that concessional assistance-only countries (Group A) be granted access to a countercyclical facility and that the use of contingent disaster financing be formalized were accepted. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, countercyclical support has been expanded to include Group A and non-OCR-eligible countries32OCR refers to Ordinary Capital Resources, which are market-based resources.(Group B) as part of ADB’s pandemic response, which includes using both Asian Development Fund grant resources and ADB concessional loan resources. ADB formally approved contingent disaster financing soon after the evaluation was issued.

ADB did not agree to the evaluation’s recommendation that in the rare cases where a regional department’s view on the macroeconomic situation of a country diverges from that of the IMF the risks involved be assessed independently of the regional department. Still, it has since strengthened the capacity of the Strategy, Policy, and Partnerships Department (SPD) to oversee PBL design before board approval. SPD has revised the PBL provisions of the Operations Manual and the relevant staff instructions, which now include a specific loan approval template and a design and monitoring framework better suited to PBL. ADB’s relationship with the IMF has been clarified and ADB’s capacity to produce a clear macroeconomic assessment strengthened, helping it support the overall quality assurance mechanism for PBL. ADB management decided against the recommendation of a separate three-year PBL operational review like the one the World Bank produces. 33World Bank Group. 2022. 2021 Development Policy Financing Retrospective: Facing Crisis, Fostering Recovery, Operations Policy and Country Services, March 16, Washington, DC.

ADB has strengthened PBL design, although the evaluation recommended ADB limit the use of process-oriented actions and articulate policy actions as substantive outputs. It recommended tailoring the design and monitoring framework (DMF)34Initial information about the project, results chain, performance indicators, data sources, and risks.so policy actions, outputs, and outcomes are more clearly linked and the analytical work underpinning PBL design and policy actions clearly referenced. These recommendations are part of the revised Operations Manual and staff instructions, but the outbreak of COVID-19 and the need to respond quickly to DMC financing needs during the pandemic has meant that implementation of these changes was initially deferred.

ADB needs to strengthen its assessment of PBL design at program completion. It also needs to focus more sharply on the role and quality of technical assistance, given its central role in the preparation and implementation of PBL. As PBL requires its own template and DMF, new approaches for assessing PBL performance need to be introduced to make sure the success rating given to completed PBLs is based on a robust evidence-based assessment of the design, especially the relevance and criticality of policy actions to development outcomes. In a single tranche PBL, policy actions have been carried out at the time of board loan approval but their relevance and criticality to the outcome should still be assessed at completion. ADB’s policy-based and project lending (on commitment bases) for the period 2000–20 is shown in Figure 2. Although non-PBO lending fell slightly during 2019–20, PBO lending increased sharply in 2020, making ADB lending highly countercyclical compared to other MDBs and the EU.

Note: PBL = policy-based lending

Source: ADB-IED.

Comments by Homi Kharas

He posed three questions: What issues affect the development effectiveness of PBL? Does the chapter capture the issues well? How is PBL linked with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which all member countries of ADB have signed on to?

PBL provides rapid financing to governments along with support for a policy reform process. The chapter describes the trade-offs involved in this process well. Financial support sometimes needs to be large and rapidly disbursed to have impact, especially during a crisis. By contrast, policy reform is often a long, slow process of incremental change and institution building. Over time, PBL has tended to address the finance objective more than the policy reform objective, as evident in the greater reliance on prior reforms; the shift to public sector management reforms within control of the ministry of finance (which, in contrast to sectoral ministries, has an incentive to deliver on reforms, as it also gets to allocate PBL resources); and the delinking of loan volume from the difficulty or cost of reform implementation.

This evolution of PBL may be positive, but it also changes the nature of the instrument. The recent trend in ADB is positive for several reasons. First, it puts countries firmly in the driver’s seat on the pace of reforms. As a development partner, it is appropriate for ADB to comment on and advise counterparts on the nature, pace, and sequencing of a reform program. It is not appropriate to use financing to bolster ADB’s own views over those of elected officials, unless there is a risk that the government program is so weak that a default could occur, or the economic context is so distorted that the loan could be immiserizing.

The chapter suggests that ADB should pay more attention to transport, energy, and water infrastructure reforms, to align with areas in which ADB has significant sectoral expertise. ADB has expertise in these areas it can and should share with governments, but it is not clear that using PBL as an instrument to force such reforms is appropriate. Adjustment loans are about providing liquidity, not forcing (or, more politely put, encouraging) specific policy reforms. Of course, a series of PBL operations can be used to structure reform incentives in the right way, but structuring the operation in a certain way is more about the pace, sequencing, and difficulty of reforms rather than the selection of one sector over another.

Second, one lesson of crisis management is that “too little, too late” has long-lasting harmful consequences. But how much is “too little”? It would be useful to have had some discussion of whether ADB’s PBLs always complemented International Monetary Fund (IMF) programs. The chapter has a brief discussion of the need for ADB to have in-house capacity to perform its own macroeconomic assessments. This recommendation may be correct, but a strong partnership, including shared analytical assessments, with other crisis lenders is possibly more important. Has ADB ever moved ahead absent an IMF program or an IMF letter of comfort on the macroeconomic front? How often is an ADB PBL part of a financing package to a government that also includes other development partners, notably the World Bank?

Data from the International Aid Transparency Initiative indicate that ADB has one of the best records of disbursement against commitments of PBL operations in response to COVID-19 of all MDBs. That is a strong testament to the value of tilting toward finance.

The chapter correctly notes it is difficult, if not impossible, to develop a strong causal link between PBL operations and actual results, given so many other factors also affect the results. PBL is likely to become even more important than it is now, partly because it provides a unique source of affordable, flexible, countercyclical, long-term development finance. The form may change toward greater pooled funding, including through country platforms (it would have been useful had the paper commented on the ongoing pilots, which will probably be supported by sector development program loans), but the sharp focus on public finance will surely remain.

- 31Asian Development Bank. 2019. Strategy 2030. Operational Plan for Priority 6. Strengthening Governance and Institutional Capacity 2019–2014. Manila.

- 32OCR refers to Ordinary Capital Resources, which are market-based resources.

- 33World Bank Group. 2022. 2021 Development Policy Financing Retrospective: Facing Crisis, Fostering Recovery, Operations Policy and Country Services, March 16, Washington, DC.

- 34Initial information about the project, results chain, performance indicators, data sources, and risks.