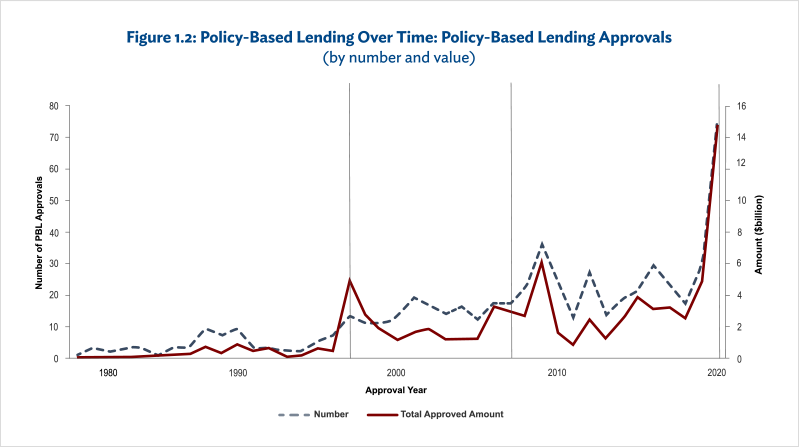

Growth in demand for PBL was initially driven by economic crises. PBL approvals surged in response to the 1990 oil price shock, spiked again during the Asian financial crisis in 1997–1998, and increased significantly in response to the global financial crisis in 2007–2009 (Figure 1.2). Nearly half of all PBL (225 loans and grants, worth about $27.1 billion) was approved in the 10 years from 2008 to 2017, with peak lending occurring around the time of the global financial crisis.12From 1978 to the end of 2017 ADB approved 451 PBL loans and grants worth approximately $55 billion. ] ADB’s response to COVID-19 in 2020, over 90% of which consisted of budget support, has been the largest single spike in demand on record.[ PBL accounted for 55% of total ADB sovereign approvals in 2020.ADB’s response to COVID-19 in 2020, over 90% of which consisted of budget support, has been the largest single spike in demand on record.13PBL accounted for 55% of total ADB sovereign approvals in 2020. However, as ADB sets a ceiling on PBL use at around 20% of overall sovereign lending, the other way it can respond to major crises is through the introduction of loans that are exempt from this ceiling and that do not necessarily contain policy reforms.14In line with other multilateral development banks (MDBs), which limit PBL use either formally or informally, ADB sets a ceiling on PBL use as a share of total sovereign borrowing. Except for its specific crisis response instruments, ADB currently limits PBL use to 20% of total sovereign lending on a 3-year rolling average basis. ADB’s PBL ceiling for concessional resources is an explicit constraint. While the introduction of crisis instruments in 2009 allowed ordinary capital resources (OCR) countries to borrow outside the ceiling, special dispensation was needed for countries eligible for concessional finance to do so because there was no such instrument for these countries. The policy does not set limits at the individual country level.In crisis periods, the share of these modalities in ADB sovereign approvals has increased sharply, showing that this type of lending modality primarily responds to country financing needs, which intensify during crisis periods, a finding common to other MDBs providing similar products.15For instance, in response to the global financial crisis, development policy financing (DPF) by the World Bank increased to about 40% of commitments and disbursements over 2009–2010.

Note: First vertical line in gray corresponds to the Asian Financial crisis in 1997; second vertical line to the global financial crisis in 2007; and the third to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.Source: Asian Development Bank Controller’s Department database.

- 12From 1978 to the end of 2017 ADB approved 451 PBL loans and grants worth approximately $55 billion. ] ADB’s response to COVID-19 in 2020, over 90% of which consisted of budget support, has been the largest single spike in demand on record.[ PBL accounted for 55% of total ADB sovereign approvals in 2020.

- 13PBL accounted for 55% of total ADB sovereign approvals in 2020.

- 14In line with other multilateral development banks (MDBs), which limit PBL use either formally or informally, ADB sets a ceiling on PBL use as a share of total sovereign borrowing. Except for its specific crisis response instruments, ADB currently limits PBL use to 20% of total sovereign lending on a 3-year rolling average basis. ADB’s PBL ceiling for concessional resources is an explicit constraint. While the introduction of crisis instruments in 2009 allowed ordinary capital resources (OCR) countries to borrow outside the ceiling, special dispensation was needed for countries eligible for concessional finance to do so because there was no such instrument for these countries. The policy does not set limits at the individual country level.

- 15For instance, in response to the global financial crisis, development policy financing (DPF) by the World Bank increased to about 40% of commitments and disbursements over 2009–2010.